We all want our open source projects to be sustainable, healthy, and successful, and having good governance influences project success more than many people realize. I’ve had governance discussions with so many open source projects over the years. When I was co-chair of the CNCF Contributor Strategy Technical Advisory Group (TAG) we did governance reviews and provided feedback for CNCF projects, and when I worked at VMware, Intel, and other companies, this was a regular topic that I discussed with employees who were leading and contributing to open source projects.

Last summer, I did a series of five blog posts on the topic of governance, so I think it’s time to revisit those posts. Here is a quick summary of each topic with a link to the post where you can learn more.

Governance Part 1: Why is it important?

Ultimately the focus of open source project governance is on the people. The roles we play, our responsibilities, how we make decisions, and what we should expect from each other as part of participating in the community. It also helps create pathways to leadership where other people can better understand the process for moving into leadership roles along with an intentional process for how the project promotes people into leadership. Being proactive about governance and related topics before something escalates into a crisis can make your projects more sustainable and reliable.

Governance Part 2: Defining Governance

In general, you should start with the simplest possible governance model and only move to something more elaborate when your project evolves to the point where the complexity is needed because otherwise you create more overhead and extra work when that time would be better spent on project development, rather than governance processes. If you don’t already have your governance and decision-making processes documented, the best place to start is by documenting and formalizing what you are already doing when you make decisions for your project. The maintainer council governance model is a simple one that many projects can use as a starting point.

Governance Part 3: New Contributors and Pathways to Leadership

Defining the roles and responsibilities for contributors, reviewers, and maintainers can help with recruiting new people into these roles. You can think of this as a ladder because contributors climb up to become reviewers and those reviewers can become maintainers. This helps set expectations for the roles and encourages people to think about how they might take on increasing responsibility within the project. As you get more of the people moving into maintainer roles, you can reduce the workload for the existing maintainers.

Governance Part 4: Creating Intentional Culture

Defining your governance / decision-making processes along with pathways to leadership are key to creating an intentional culture for your project that encourages participation and contributions from others. However, just documenting your governance process and setting expectations in writing isn’t enough. You should also be role modeling good behavior and helping others understand what behavior is appropriate within your project. It’s important to remember that tolerating bad behavior unwittingly sets the expectation that this behavior is acceptable in your project, which can drive new contributors away. Robust governance documentation that incorporates your code of conduct, charter (or similar statement of mission, scope, and values), and includes clear processes for dealing with conflict can help make your project more sustainable over time.

Governance Part 5: Overall Ownership of a Project

While there are a few exceptions, open source projects usually have an individual, company, or foundation controlling the trademarks, project infrastructure, and other assets. This overall ownership structure often impacts how the project is governed on a day to day basis and how the project is perceived by others. Neutral foundations provide a level playing field where contributors can contribute as equals regardless of whether they are contributing on behalf of a company or as an individual. This structure allows companies to collaborate together in a neutral environment where no single company is in control of the project.

I hope you enjoyed this short summary, and if you want feedback or help with governance or related OSPO topics, I’m available for consulting engagements.

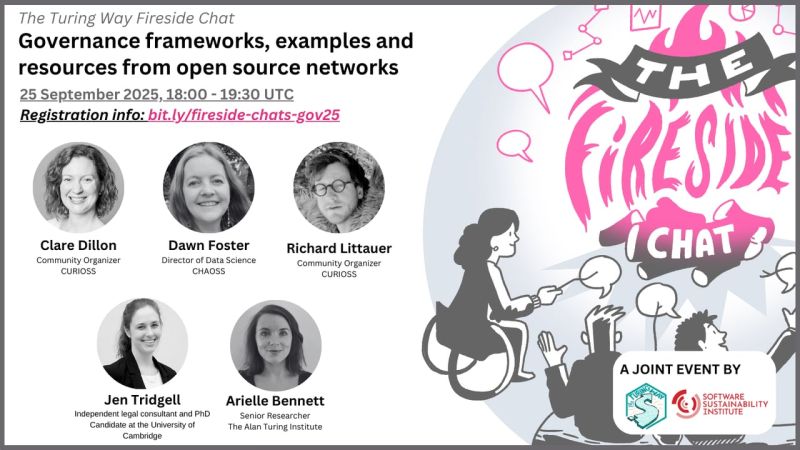

Additional Resources:

- 4 Minute Governance Overview Video

- Good Governance Practices for Healthy Open Source Projects (video)

- The Open Source Way Guidebook section on Governance

- CNCF guides, resources, and templates for governance

- SustainOSS Governance Readiness Checklist

- What can your OSPO do about power dynamics, rug pulls, and other corporate impacts on OSS sustainability?